A hostage is a captive who is held by the captor as security for something. It’s a very old practice. Sometimes it’s patently criminal, a kidnapper kidnapping for ransom. Sometimes it’s a bargain, as when England gave over two aristocrats as security for returning Cape Breton to France upon the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748. To the pedant, these things matter; in 1911 the Encyclopaedia Britannica primly observed:

In May 1871, at the close of the Paris Commune, took place the massacre of the so-called hostages. Strictly they were not ‘hostages’, for they had not been handed over or seized as security for the performance of any undertaking or as a preventive measure…

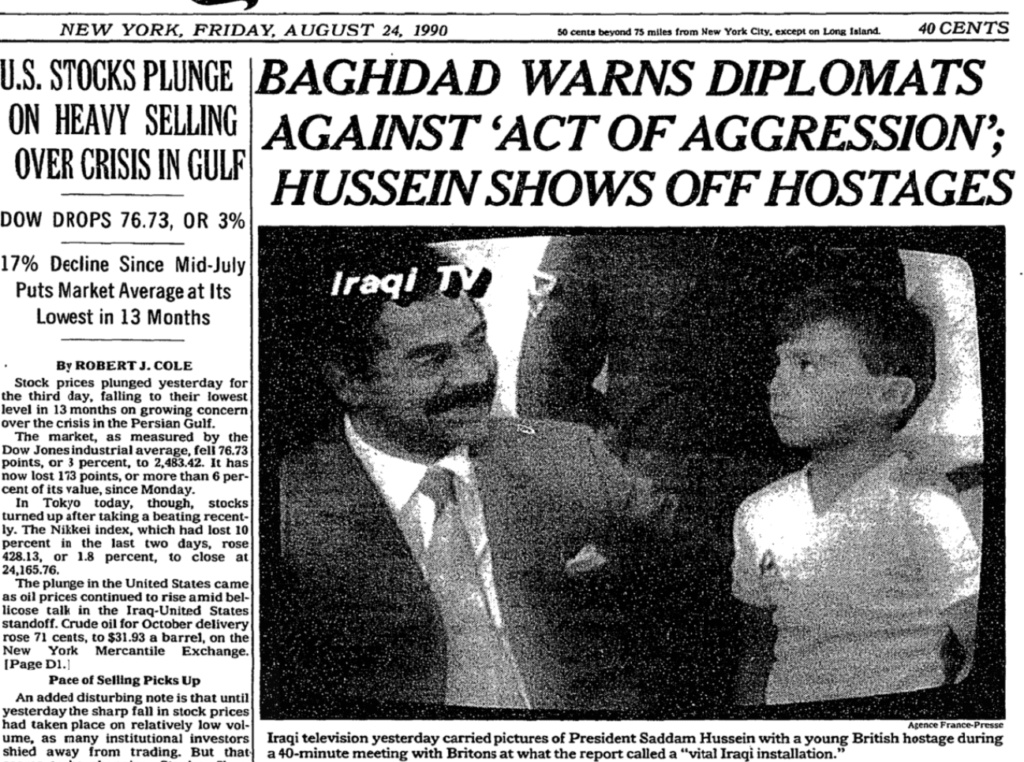

On 23 August 1990, President Hussein conducted one of his bizarrely homey tv appearances, trying to chat warmly with British citizens caught up in Kuwait. The next day under the headline “Confrontation in the Gulf; Iraqi TV Shows a Smiling Leader With Grim-Faced British Captives”, a typically fastidious New York Times reported:

The Iraqi authorities have said that Westerners trapped in Iraq and occupied Kuwait will not be allowed to leave until the threat of war with the United States and other countries ends. Although Iraq has denied that the foreigners are hostages, it has moved some of them to military and industrial installations to serve as shields against attack.

If a world leader can’t be certain about what crimes he is committing, what hope the common-or-garden bank robber? At what stage of a failed robbery does one opt to turn hapless bystanders from victims to hostages?

And from hostages to what? On 23 August 1973, a bank robbery did go wrong and captives were held hostage for days. Later, the hostages not only didn’t testify against the robbers; they raised money for the defence.

The robbery took place in Norrmalmstorg Square and the psychiatrist assisting police called the reaction Norrmalmstorgssyndromet. The rest of us call it “Stockholm syndrome”.