The 1916 presidential campaign saw the appearance on the campaign trail, or perhaps track, of the Hughes special, a train of women supporting Hughes. It was not all easy going. The Topeka State Journal for 28 October 1916 reported ox-gall in a Kansas City auditorium – “KC auditorium reeking with odor for Republicans” – and a “near-riot” at the railway station where hecklers sought to break up the Hughes parade. In a delightful show of gender solidarity from the other side of the floor, the women of the pro-Wilson Trades Union league vigorously denounced both actions.

Wilson beat Hughes but he hadn’t beaten all his Hugheses. Today is a day for the other Hughes.

On 28 October 1934 the New York Times reviewed the memoirs of David Lloyd George, the fiery Welsh leader of the UK during the Great War, under the subheading “The third volume of his memoirs is severely critical of President Wilson and others”. What follows is an Antipodean complement to a Welshman’s narrative.

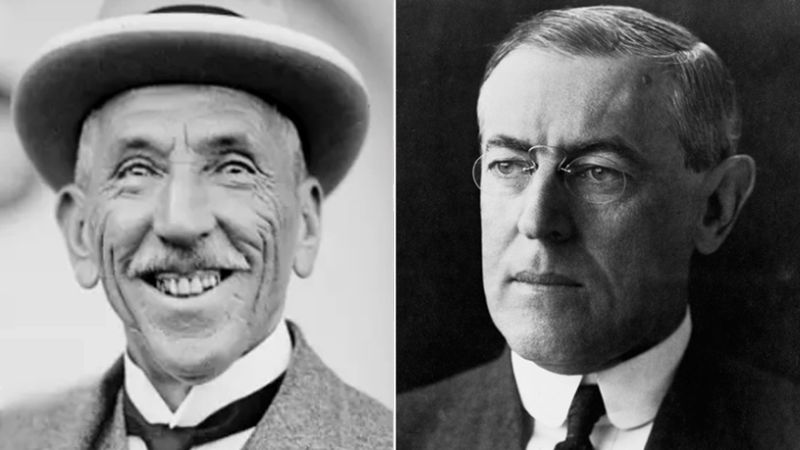

Welshman Billy Hughes arrived in Australia in his 20s. After a decade in a colonial legislature he would sit in Australia’s parliament from its creation in 1901 until his death on 28 October 1952. In 1952, Australia had less than nine million people and one in twenty of them lined the Sydney streets for his funeral. Like Lloyd George, Hughes led his nation in war and represented his nation at Versailles. He and Lloyd George had the curious distinction of chatting in Welsh in the British war cabinet and at Versailles.

Few Australians recall Hughes. To the extent he is recalled at all, he is remembered for his adherence to the White Australia Policy. The story is more complex.

Much of our learning about Versailles is Eurocentric, with the usual picture being the idealism of a foreign Wilson against the realpolitik of a local Clemenceau. Hughes’s presence at Versailles is a channel for a different perspective.

In the Pacific, the new kid on the block was Japan. It had sided with the Entente during the war, occupying German possessions in the Pacific and east Asia and increasing its influence in east Asia.

Japan arrived at Versailles with two interests, territory and race. Prime Minister Hughes and President Wilson clashed on both. They were very different men. One story has many versions. One is Wilson proclaiming “I would have you to know, Mr Hughes, that I represent 90 million live Americans!” and Hughes replying “I’d have you know, Mr President, that I represent 60,000 dead Australians!” Another has a good ring of truth with Wilson the southern son of a preacher man using biblical and distinctly American imagery to describe Hughes as “a pestilential varmint”.

As to territory, Japan was successful. By Treaty article 156, Germany renounced its interests in Shantung in favour of Japan and by the South Seas Mandate, a control of islands to the north of Papua New Guinea. It succeed notwithstanding spirited opposition from Hughes, which Lloyd George recalled as:

Wilson: “Mr Hughes, am I to understand that if the whole civilised world asks Australia to agree to a mandate in respect of these islands, Australia is prepared still to defy the appeal of the whole civilised world?”

Hughes: “That’s about the size of it, President Wilson”.

From a modern viewpoint, Hughes’s position is easily and misleadingly placed wholly upon racism. Hughes was primarily concerned with stopping Japanese expansion. He failed in this and in subsequent attempts. It may have been appropriate that he failed. It has also to be observed a generation later, Shantung was a province subjected to the Japanese “three alls” policy, “kill all, burn all, loot all”, while the US commenced its Pacific campaign in the mandate later known as the Marshall and Gilbert Islands.

More interesting from a post-World War II and Declaration of Human Rights world was Japan’s proposal of a racial equality clause. On the one hand, the immediate priority of Japan was its sphere of influence. On the other, it had a decades-long interest in equalising what it held to be the unequal treaties with the great white nations in the 1850s. In pursuit of the latter, it proposed:

The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord as soon as possible to all alien nationals of states, members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality.

The orthodox history is that the proposal failed first because of the vigorous opposition of Hughes and second because the Japanese did not appreciate that the whole colonial edifice depended upon an acceptance of the supremacy of colonialists over the colonised. Wilson had flagged colonialism in his Fourteen Points but did not press it at the conference.

As to the first, there is no doubt that Hughes was an implacable supporter of a policy which had been in place since Australia’s creation, the White Australia policy. But there was another theme. In saying – as he did – that a state had the right “to determine the conditions under which persons shall enter its territories”, he was saying no less than countless politicians of various races have persistently and often popularly maintained. It must also be recalled that Wilson had little personal interest in the clause.

As to the second, it is as well to remember during the conference that Japan brutally suppressed the March 1st Movement, the Korean protest against their imperial masters and that the US approach from Wilson down was to refuse Korea assistance or recognition.

None of which is to celebrate Hughes or to denigrate Wilson. As we tend to demand of statesmen that they act in a statesmanlike manner we tend to forget that their status derives from the state which they represent, and they have no mandate – to transpose a topical word – to deviate from the state line.

As for Hughes, he returned to his state a champion and survived electorally as prime minister to 1923. As for Wilson, he was sick and facing domestic challenges. The most famous, the Volstead Act aka the National Prohibition Act, was vetoed by Wilson on a Monday, a veto overridden by the house later that day and overridden by the senate on the Tuesday aka 28 October 1919, when it became law.