Countries forged by revolution like foundation days as they are good for creating a sense of stability. But it can be tricky. Remember John Adams’ letter to wife Abigail on 3 July:

The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival.”

Oops.

It’s even more difficult when a country is reinventing itself after civil wars including the assassination of a would-be king whose pastime was calendar reform and whose adoptive son and heir eventually won. Pity then Roman poets and scholars in the half century after Julius Caesar’s assassination.

Two examples.

First, Marcus Terentius Varro. He fought for Pompey against Caesar; he was pardoned and made librarian by Caesar; he was proscribed by Mark Antony on Caesar’s death and lost much of his own library; and slowly got back in favour as Caesar’s heir Octavian pushed Rome from republic to empire.

With this at his back and confronted with Caesar’s own reform – the Julian calendar – Vallo consolidated a chronology based on years “ab urbe condita”, or “from the founding of the city”, usually abbreviated AUC. In our language, he put the foundation date at 21 April 753 BCE.

Secondly, Ovid. Move from Caesar’s assassination a couple of generations to 8 CE. Octavian, now the emperor Augustus, has just banished Ovid for what Ovid would wistfully refer to as his carmen et error, his poem and mistake. A chance to get back in the good books with the emperor was a work-in-progress, Fasti, essentially a monthly calendar comprised of poems.

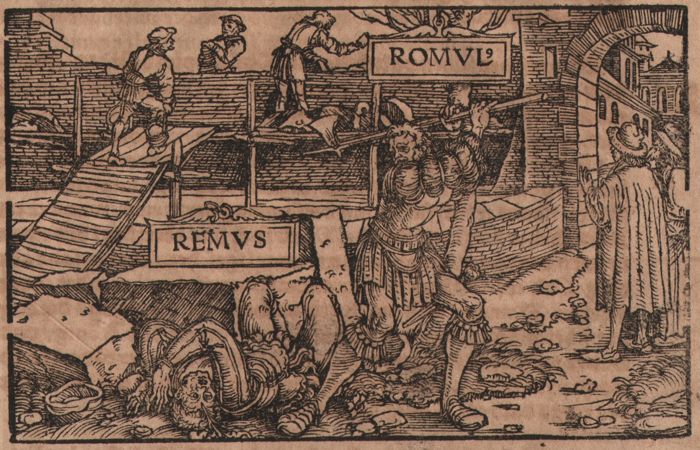

The problem for the poet was that 21 April 753 BCE was a day of fratricide. On it, Romulus killed Remus. While there were different versions, the most recent for Ovid – and for Augustus – was Livy’s Histories, or, now that Vallo had done the legwork, Ab Urbe Condita Libri.

Livy recorded the “more common account” as Romulus himself killing Remus. No henchmen, no angry crowds to whip up. Fine for republican Rome, but this was not on in imperial Rome. Kings don’t kill kin.

Ovid dealt with the problem, anticipating a meddlesome priest and a monarch’s crocodile tears by 1100 years:

… the citizens laid foundations,

And the new walls were quickly raised.

The work was overseen by Celer, whom Romulus named,

Saying: ‘Celer, make it your care to see no one crosses

Walls or trench that we’ve ploughed: kill whoever dares.’

Remus, unknowingly, began to mock the low walls,

saying: ‘Will the people be safe behind these?’

He leapt them, there and then. Celer struck the rash man

With his shovel: Remus sank, bloodied, to the stony ground.

When the king heard, he smothered his rising tears,

And kept the grief locked in his heart.”

But death comes in the end, and by his Ovid hadn’t got back in favour and hadn’t taken Fasti beyond June. At least he didn’t have to worry about writing up a month named for his churlish master’s adoptive father.