A fallback for disease-naming is, or at least has been until very recently, choosing the place of first detection. As WHO notes on its website entry for Hendra Virus Infection:

HeV was identified during the first recorded outbreak of the disease in the Brisbane suburb of Hendra, Australia, in 1994.

Of course, things can go south very quickly, and in 1918 they did.

Around the end of the Great War, a particularly nasty outbreak of Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 took hold. Censors still ran newspapers, and no-one wanted bad news reported on the home front. Spain was neutral and its press lacked chains. The press reported, its reports were re-reported in war-weary countries to the north and over the pond, and so the Spanish flu was born with Spain its epicentre.

epi- is “near/at/upon” and pan- is “all”; with demos being “people”, an epidemic which spreads far enough becomes a pandemic but an epicentre stays put; a pancentre is an etymological oxymoron.

A century after the Spanish flu, sensibilities like everything else have become both immediate and global. A place is capable of being branded epicentre to a pandemic in an instant.

In 2009, another outbreak of Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 took hold. The first reports were, uncontroversially, from Mexico but in a case of the Spanish speaker’s revenge, “swine flu” was just fine.

At least, things were fine until cases reached Israel, where getting “swine flu” was not only dangerous but deeply offensive for Jew and Arab alike. Israel’s Health Ministry went with, but soon backed down from, “Mexican flu”.

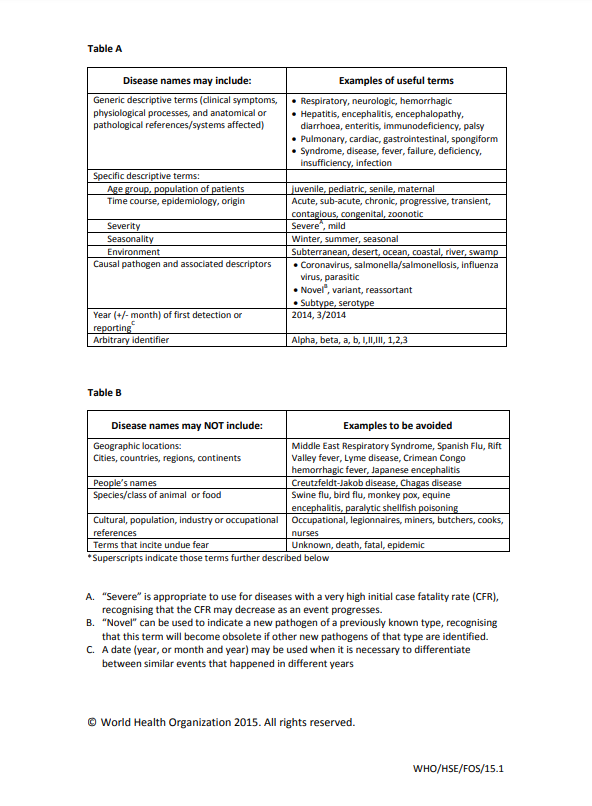

In May 2015, WHO tackled the politically pathogenic world of disease-naming and released its best practice:

Just over four years later, on 31 December 2019, WHO received its first information from Wuhan. What is fascinating is the politics and the practices that led to the development of the neologism “COVID-19” some six weeks later.

First, the media release:

The media release is both accurate and inaccurate. It is accurate, in the sense that on 5 January 2020, WHO released the text. It is inaccurate, in that no-one on 31 December 2019 or 5 January 2020 was using “COVID-19”; the heading to this media release has been, clearly enough, changed since the time of the release.

At the time this post is being written, Wikipedia says that “Wuhan flu” may be “an informal term for COVID-19, mostly seen as indicative of the xenophobia related to the pandemic”.

Whatever the case today, in January and early February 2020, the first weeks after the discovery, Wuhan was widely referred to. On 2 February, the New York Times, hardly the epicentre of American China-bashing, reported:

The Wuhan coronavirus spreading from China is now likely to become a pandemic that circles the globe, according to many of the world’s leading infectious disease experts.

In fairness, Wiktionary has:

Since the coining of the more formal names SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 words like Wuhan flu, Wuhan virus, China virus and Chinese virus are sometimes considered offensive…

The operative word is “since”. In early 2020, there was nothing controversial. No, commentators were not using best practice, but they were using a practice that had been in place for at least a hundred years.

But these were not simple times. While January 2020 was a relatively good month for US/China trade ties, there was a complex background, President Trump was going into a re-election year, and allegations that China was cosying up to WHO were already in play.

On 11 February 2021, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses and WHO announced, respectively, the name for the new virus and the name for the disease it was causing:

- severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, or SARS-CoV-2; and

- coronavirus disease, or COVID-19.

As can be seen, WHO’s name was a textbook application of its own best practices and most famous neologism in world history is born.