Our industrial revolutions so far are mechanization, mass production, automation and robotization. The fifth revolution, we keep telling ourselves, will be a rehumanization, an age when we all reap the benefits of these gains.

Whether such optimism is justified, the one consumer durable for at least three of the ages and the one we will hold onto, literally, as we stumble into the fifth, is the telephone.

On 18 November 1963 something rather profound happened. On 18 November 1963, Bell System introduced the push-button telephone after years of customer testing. It was called “Touch-Tone”, and the US Patent and Trademark Office record shows that the application for the name was made almost three years before. Nor was it designed in secret. The Bell System exhibit in the 1962 Seattle World Fair shows the push-button phone alongside the Bell solar battery, direct distance dialling and the “Electronic Central Office”.

The dominant phone model for much of the 20th century had been the rotary telephone. The user inserted a finger in a fingerhole corresponding to a digit and rotated the dial clockwise until the finger stop was reached. The finger was withdrawn, the dial was released and returned to its start, and the user inserted a finger to dial the next digit.

The shift from rotary dialling to “Touch-Tone” was a shift to an underlying technology called “dual tone multi-frequency” or DTMF. The “dual tone” in the technology manifested itself in 8 x 2 or 16 tones, which in turn manifested itself into 16 keys.

Were the shift simply from the finger to the keypad, there wouldn’t be much of a tale. It would be a mere nostalgia for a memorable Morse code.

But there was another thing happening at the same time. We were running out of alphanumerics.

In 1963, if one person wanted to give another person their phone number, they would give a physical exchange address and a number. We know this because Marvin Gaye, Mickey Stevenson and George Gordy the year before had written a song for the Marvelettes. The female singer invites a male to ring her on “Beechwood 4-5789” “to have a date, any old time”. The male object in the song was being invited to rotary dial BE for Beechwood and 4-5789 for the phone linked to the Beechwood exchange.

Bell Systems had been working on this too, and was in the process of instigating another change, from alphanumeric dialling to all-number dialling.

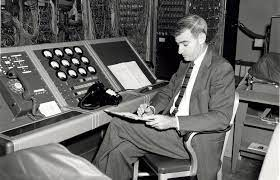

Enter John Karlin, an accomplished violinist from South America who did his research at Harvard in the emerging world of psychoacoustics. By the middle of the century he was head of Human Factors Engineering at Bell System and was charged with the question, what keypad will work best?

In essence and at risk of conflation of work over many years, Karlin’s team had to make two profound changes in phone technology useable for the rest of us. We had to be weaned from letters and we had to be pushed into numbers.

The first thing that happened is that four of the sixteen tones went. At least for we commoners. There may well be A, B, C and D keys on the right of Pentagon phones but the rest of us will never know.

This left 10 digits and two extras. The extras have become our star and hash.

But what of the digits? Around the time Karlin was working, the calculator was being developed and its layout is unchanged today. Look at the numbers to the right of the letters on your keyboard: 1, 2, 3 on the bottom and upward it goes.

But this is not how our phones have been laid out. It was Karlin’s team who found that while speed and accuracy were much of a muchness and while we we humans have a bottom-up approach to numeracy, we prefer our orality to follow our words, using our numbers as we use our letters, left to right and top to bottom.

So it remains today.

As for Karlin, he did receive some media attention. As the New York Times recorded in a 2013 obituary:

“One day I was at a cocktail party and I saw some people over in the corner,” Mr. Karlin recalled in a 2003 lecture. “They were obviously looking at me and talking about me. Finally a lady from this group came over and said, ‘Are you the John Karlin who is responsible for all-number dialing?’ ”

Mr. Karlin drew himself up with quiet pride.

“Yes, I am,” he replied.

“How does it feel,” his inquisitor asked, “to be the most hated man in America?”