The answer to the question what is the difference between “insurrection” and “revolution” depends, of course, on which side you are. The American colonies were not slow to coin their rebellion a “revolution” and they were sensible to do so. The word “revolution” in the 1770s did not necessarily mean the visceral violence of the French revolution. The English themselves at the end of the previous century had been quick to adopt their own constitutional turmoil as a “glorious revolution”.

On 30 November 1831, Nat Turner was arrested for leading a slave rebellion in Southampton, Virginia. He and many others were soon executed. The event, rightly, features prominently in a narrative about US slavery. Today is not a look at the event but a look at the development of the history of that rebellion.

The local press reports generally described the affair as an insurrection. Leaving to one side the rhetoric to be expected in newspapers providing news for white slaveowners, the flavour is lowkey and one suspects that the press took the view that under- rather than over- reporting was the order of the day and calm would prevail.

The local press also touch on two themes of slavery and American slavery in particular which often take second place to the prevailing moral argument. The first arose from the fact that Turner was a preacher. Some commentators in the local press pointed out, for them, the obvious solution. No more black preachers. The second is the economic issue. Some commentary touches on the “yes but” argument, essentially “Slaves are property, property is sacred, if slavery is abolished our property is being confiscated”.

Almost three decades later, white abolitionist John Brown raided the US arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in Virginia, in an attempt to provoke a slave rebellion. On the eve of America’s most costly war, New York’s Weekly Anglo-African recalled Turner’s efforts and editorialised:

So, people of the South, people of the North! men and brethren, chose ye which method of emancipation you prefer – Nat Turner’s or John Brown’s?

President Lincoln issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in the second half of 1862. A copy of the Smoky Hill and Republican Union – an unreservedly anti-slavery publication – reflects on Richmond’s reaction under the headline “The Proclamation in Secessia”, observing:

They very much fear the inauguration of negro insurrections from the effects of the new policy. They repicture the scenes of the Nat Turner insurrection in Southampton county, Virginia, in 1831, when fifty-five white persons were murdered by enraged negroes.

The author makes the point that if slaves are incited to commit excess, the rebels only have themselves to blame “in throwing off the only safeguard they had for protection from any belligerent – the National Government.”

The often vicious complexity of the war itself, of emancipation, of reaction, and of separation-but-equality would follow.

Come 1931 and the centenary celebration, the mainstream white press was, as best I can see, almost completely silent. One exception was the Indianapolis Times, which prided itself for crusading journalism and which had taken a Pulitzer in 1928 for exposure of KKK involvement in local politics. It ran short piece advertising a centennial observance at a local workers club.

For the radicals, the position was different. Nat Turner’s name appeared frequently in the Daily Worker, who put the rebellion in class terms and held that Turner was “put to death by the bourgeoisie of the south”. Yet another century on it can be said with confidence that Scarlett O’Hara’s family would have been more offended to be called bourgeoisie than traitorous.

The black press was a different place. The Omaha Guide ran a frontpage story on the man who “struck a blow at the vicious system of slavery… that upset the whole smug and complacent attitude of the American in the period prior to the Civil War.”

Indeed, Turner’s name was not reserved for centenaries. The Enterprise was a Seattle newspaper founded in 1920 and a 1927 copy holds a short story “Spokesmen of the Race” in which Turner is listed as one of the “eloquent and courageous spokesmen” who “advocated the extermination of slavery by the use of force”. The adjacent story has a delightful cross-cultural reference headed “Watch the Jews”. It is about Aaron Sapiro’s great lawsuit against Henry Ford and his antisemitism:

Save from the viewpoint of right and justice it doesn’t matter much to us who wins the suit; but it is a healthy lesson for us to absorb that the Jews are puffing over with pride… They’re go-getters! When some one injures a Jew he’s going to look right square into the muzzle of a gun loaded with serious consequences. It wouldn’t hurt if we were more like the Jews.

A quarter century later, many black activists were go-getting a civil rights movement.

For its part, the Arkansas State Press has a fascinating cross-cultural reference. Black communist politician Benjamin Davis had just been jailed and a 1951 commentator compares Davis to Turner, referring to a past of “the ‘Dred Scott’ decision, Days of the fugitive slave laws, Days of the Black codes, Days of Thought Police”. While the civil branch of the Japanese secret police was well known in post-WWII America as the “Thought Police”, it is more likely an ironic reference to Orwell’s anti-communist 1984, published in 1949.

The question “Can Nat Turner be owned?” has been answered, for now, by history. Another question is “Who owns Nat Turner’s narrative?”

In a world where memory is able to be captured as a brand, this is an important question, and litigation about the person “Martin Luther King Jr” is an example.

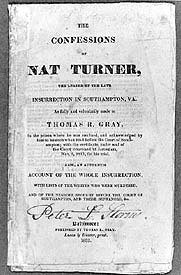

At a wider level, there is the question, “Which community can lay claim to a dead person’s story?” A white William Styron, the author of Sophie’s Choice, wrote The Confessions of Nat Turner and it won a Pulitzer Prize in 1967. The work was heavily criticised by many black commentators for a variety of reasons. The work itself drew on an asserted confession by Turner to a white lawyer, itself published under the same title in 1831, and itself republished by a number of black outlets in previous generations. Styron’s friend James Baldwin, who had suffered a different version of the same criticism when Another Country was published, wryly and correctly predicted things when he told a reporter “Bill’s going to catch it from both sides”.

Race and sexuality are perennially fascinating for people who like to hold firm views. I suspect that this may be because our race and our sexuality, unlike our bodies and our minds, are incapable of being owned by others.

I don’t know why Baldwin chose the title “Another Country” although it conjures up Marlowe’s Jew of Malta:

Friar Barnardine. Thou hast committed –

Barabbas. Fornication: but that was in another country;

And besides, the wench is dead.

In publicity for the 2016 documentary I Am Not Your Negro, there is half-century old footage of Baldwin saying “The future of the negro in this country is precisely as bright or as dark as the future of the country.” Baldwin and MLK differed on a number of things and Baldwin’s own move to militancy was in some ways a rejection of King’s hope in brotherly love. The document was shown at the film festival of the City of Brotherly Love on 30 October 2016.